Blitzkrieg

Blitzkrieg (German, "lightning war"; listen (help·info)) is an anglicised word[1][2][3][Notes 1] describing all-motorised force concentration of tanks, infantry, artillery, combat engineers and air power, concentrating overwhelming force at high speed to break through enemy lines, and, once the lines are broken, proceeding without regard to its flank. Through constant motion, the blitzkrieg attempts to keep its enemy off-balance, making it difficult to respond effectively at any given point before the front has already moved on.

During the interwar period, aircraft and tank technologies matured and were combined with systematic application of the German tactics of infiltration and bypassing of enemy strong points.[7] When Germany invaded Poland in 1939, Western journalists adopted the term blitzkrieg to describe this form of armoured warfare.[8] Blitzkrieg operations were very effective during the campaigns of 1939–1941. These operations were dependent on surprise penetrations (e.g. the penetration of the Ardennes forest region), general enemy unpreparedness and an inability to react swiftly enough to the attacker's offensive operations. During the Battle of France, the French, who made attempts to re-form defensive lines along rivers, were constantly frustrated when German forces arrived there first and pressed on.[9]

Academics since the 1970s have questioned the existence of blitzkrieg as a coherent military doctrine or strategy. Many academic historians hold the idea that the German armed forces adopted "blitzkrieg" as an offensive doctrine to be a myth. Others continue to use the word to describe the style of breakthrough warfare practised by the Axis powers of this period, even if it were not a formal doctrine. The concepts of Blitzkrieg form the basis of present-day armoured warfare.

Operations

[edit]Poland, 1939

In Poland, fast moving armies encircled Polish forces (blue circles), but the blitzkrieg idea never really took hold – artillery and infantry forces acted in time-honoured fashion to crush these pockets.

Despite the term blitzkrieg being coined by journalists during the Invasion of Poland of 1939, historians Mathew Cooper and J. P Harris generally hold that German operations during it were more consistent with more traditional methods. The Wehrmacht's strategy was more in line with

Vernichtungsgedanken, or a focus on envelopment to create pockets in broad-front annihilation. Panzer forces were dispersed among the three German concentrations

[62] without strong emphasis on independent use, being used to create or destroy close pockets of

Polish forces and seize operational-depth terrain in support of the largely un-motorized infantry which followed.

While early German tanks, Stuka dive-bombers and concentrated forces were used in the Polish campaign, the majority of the battle was conventional infantry and artillery based warfare and most Luftwaffe action was independent of the ground campaign. Matthew Cooper wrote that

[t]hroughout the Polish Campaign, the employment of the mechanised units revealed the idea that they were intended solely to ease the advance and to support the activities of the infantry....Thus, any strategic exploitation of the armoured idea was still-born. The paralysis of command and the breakdown of morale were not made the ultimate aim of the ... German ground and air forces, and were only incidental by-products of the traditional maneuvers of rapid encirclement and of the supporting activities of the flying artillery of the Luftwaffe, both of which had as their purpose the physical destruction of the enemy troops. Such was the

Vernichtungsgedanke of the Polish campaign.

[63]

John Ellis explained that “...there is considerable justice in Matthew Cooper's assertion that the panzer divisions were not given the kind of

strategic mission that was to characterize authentic armoured blitzkrieg, and were almost always closely subordinated to the various mass infantry armies.”

[64]

Steven Zaloga states: “Whilst Western accounts of the September campaign have stressed the shock value of the panzers and Stuka attacks, they have tended to underestimate the punishing effect of German artillery on Polish units. Mobile and available in significant quantity, artillery shattered as many units as any other branch of the Wehrmacht.”

[65]

[edit]Western Europe, 1940

German advances during the Battle of Belgium

The German invasion of France, with subsidiary attacks on

Belgium and the

Netherlands, consisted of two phases, Operation Yellow (

Fall Gelb) and Operation Red (

Fall Rot). Yellow opened with a feint conducted against the Netherlands and Belgium by two armoured corps and

paratroopers. The Germans had massed the bulk of their armoured force in Panzer Group von Kleist, which attacked through the comparatively unguarded sector of the

Ardennes and achieved a breakthrough at the

Battle of Sedanwith air support.

[66]

The group raced to the coast of the

English Channel at Abbeville, thus isolating the

British Expeditionary Force,

Belgian Army, and some divisions of the

French Army in northern France. The armoured and motorized units under Guderian and Rommel initially advanced far beyond the following divisions, and indeed far in excess of that with which German high command was initially comfortable. When the German motorized forces were met with a counterattack at

Arras, British tanks with heavy armour (Matilda I & IIs) created a brief panic in the German High Command. The armoured and motorized forces were halted, by Hitler, outside the port city of

Dunkirk, which was being used to evacuate the Allied forces.

Hermann Göring had promised the Luftwaffe would complete the destruction of the encircled armies, but aerial operations did not prevent the evacuation of the majority of Allied troops (which the British named

Operation Dynamo); some 330,000 French and British were saved.

[67]

Overall, Yellow succeeded beyond what most people had expected, despite the fact that the Allies had 4,000 armoured vehicles and the Germans 2,200, and the Allied tanks were often superior in armour and caliber of cannon.

[68] The French and the British used tanks in their pre-blitzkrieg 'traditional' role of assisting infantry and dispersed across the whole army so there was not concentration of tanks, while the blitzkrieg method of concentrating tanks, even less in number and less capable in ability, led to victorious success.

German advances during the Battle of France

This left the French armies much reduced in strength (although not demoralized), and without much of their own armour and heavy equipment. Operation Red then began with a triple-pronged panzer attack. The XV Panzer Corps attacked towards

Brest, XIV Panzer Corps attacked east of Paris, towards

Lyon, and Guderian's XIX Panzer Corps completed the encirclement of the

Maginot Line. The defending forces were hard pressed to organize any sort of counter-attack. The French forces were continually ordered to form new lines along rivers, often arriving to find the German forces had already passed them. When Colonel de Gaulle did organize a counter-attack with superior French tanks, he did not have the air support to gain the upper hand and had to retreat.

Ultimately, the French army and nation collapsed after barely two months of mobile operations, in contrast to the four years of trench warfare of the First World War. The French president of the Ministerial Council, Reynaud, attributed the collapse in a speech on 21 May 1940:

The truth is that our classic conception of the conduct of war has come up against a new conception. At the basis of this...there is not only the massive use of heavy armoured divisions or cooperation between them and airplanes, but the creation of disorder in the enemy's rear by means of parachute raids.

In actual fact, the German army had not used paratroop attacks in France. The one major paratrooper attack was used earlier in Holland to capture a bridge and a number of small-scale glider-landings were conducted in Belgium to capture terrain dominating bottle-necks on planned routes of advance prior to the arrival of the main ground forces (the most renowned being the landing on the Belgian border-fort of Eben-Emael). The real cause for the fall of France was the blitzkrieg method of warfare.

[edit]Soviet Union: the Eastern Front: 1941–44

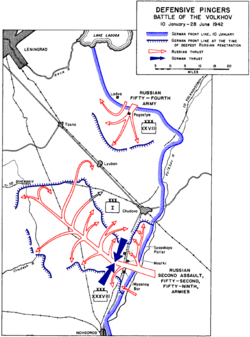

After 1941–42, armoured formations were increasingly used as a mobile reserve against Allied breakthroughs. The black arrows depict armoured counter-attacks.

Use of armoured forces was crucial for both sides on the Eastern Front.

Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the

Soviet Union in 1941, involved a number of breakthroughs and encirclements by motorized forces. Its stated goal was “to destroy the Russian forces deployed in the West and to prevent their escape into the wide-open spaces of Russia.”

[69] A key factor was the surprise attack which included the near annihilation of the total Soviet airforce by simultaneous attacks on airfields. On the ground, four giant panzer armies encircled surprised and disorganized Soviet forces, followed by marching infantry which completed the encirclement and defeated the trapped forces. The first year of the

Eastern Front offensive can generally be considered to have had the last successful major mobile operation for the German army.

After Germany's failure to destroy the Soviets before the winter of 1941, the strategic failure above the German tactical superiority became apparent. Although the German invasion successfully conquered large areas of Soviet territory, the overall strategic effects were more limited. The Red Army was able to regroup far to the rear of the main battle line, and eventually defeat the German forces for the first time in the

Battle of Moscow.

[70]

In the summer of 1942, when Germany launched another offensive in the southern

USSR against

Stalingrad and the

Caucasus, the Soviets again lost tremendous amounts of territory, only to counter-attack once more during winter. German gains were ultimately limited by

Hitler diverting forces from the attack on Stalingrad itself and seeking to pursue a drive to the Caucasus oilfields simultaneously as opposed to subsequently as the original plan had envisaged. Even so, the

Wehrmacht was becoming overstretched. By winning operationally, strategically it could not keep up the momentum as the superiority of the Soviet Union's industrial base and economy began to take effect.

[70]

In the summer of 1943 the

Wehrmacht launched another combined forces offensive operation –

Zitadelle (Citadel) – against the Soviet salient at

Kursk. Soviet defensive tactics were by now hugely improved, particularly in terms of artillery and effective use of air support. All the same the

Battle of Kursk was marked by the Soviet switch to offence and the use of the revived doctrine of deep operations. For the first time the blitzkrieg was defeated in summer and the opposing forces were able to mount their own, successful, counter operation.

[71]

By the summer of 1944 the reversal of fortune was complete and

Operation Bagration saw Soviet forces inflict crushing defeats on Germany through the aggressive use of armour, infantry and air power in combined strategic assault, known as

deep operations.

[edit]Western Front, 1944–45

As the war progressed, Allied armies began using combined arms formations and deep penetration strategies that Germany had used in the opening years of the war. Many Allied operations in the Western Desert and on the Eastern Front relied on massive concentrations of firepower to establish breakthroughs by fast-moving armoured units. These artillery-based tactics were also decisive in Western Front operations after

Operation Overlord and both the British Commonwealth and American armies developed flexible and powerful systems for utilizing artillery support. What the Soviets lacked in flexibility, they made up for in number of multiple rocket launchers, cannon and mortar tubes. The Germans never achieved the kind of fire concentrations their enemies were capable of by 1944.

[72]

After the Allied landings at

Normandy, Germany made attempts to overwhelm the landing force with armoured attacks, but these failed for lack of co-ordination and Allied air superiority. The most notable attempt to use deep penetration operations in Normandy was at

Mortain, which exacerbated the German position in the already-forming

Falaise Pocket and assisted in the ultimate destruction of German forces in Normandy. The Mortain counter-attack was effectively destroyed by U.S. 12th Army Group with little effect on its own offensive operations.

[73]

Germany's last offensive on its Western front,

Operation Wacht am Rhein, was an offensive launched towards the vital port of

Antwerp in December 1944. Launched in poor weather against a thinly held Allied sector, it achieved surprise and initial success as Allied air power was stymied by cloud cover. However, stubborn pockets of defence in key locations throughout the Ardennes, the lack of serviceable roads, and poor German logistics planning caused delays. Allied forces deployed to the flanks of the German penetration, and as soon as the skies cleared, Allied aircraft were again able to attack motorized columns. The stubborn defense by US units and German weakness led to a defeat for the Germans.

[74]